Making Tar at Kiln Hollow on the Bryant Creek

Click to enlarge

David Haenke of Brixey says, “This land loves pine, and pine loves this land.” In 1853-54 B.F. Shumard, of the State Geological Survey, estimated a pine forest of over ninety square miles along mid to upper Bryant Creek. He told of many sawmills producing lumber that was hauled by ox team to Springfield and Bolivar.

Tar Kiln Hollow, where they made tar in kilns, was near an old wagon road along the Bryant. A kiln is an oven for heating materials without letting them burn up.

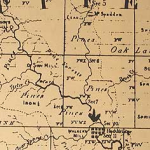

This part of an 1841 Geological Map of Ozark County shows “Pines” in the Rockbridge and Cane Bottom Hollow area. This was before large-scale logging.

Large-scale logging of pine began around here when the railroad came to Mountain Grove in 1880. Most likely, the land around Tar Kiln Holler was heavily logged between 1922 and 1929. That’s when the Big Mill, literally a small town with the mill as its center, operated along Cane Bottom Hollow. That’s where the #95 Bridge crosses the Bryant today.

Logging left stumps with sap-filled heartwood, good for making tar. People used tar for waterproofing all kinds of things, from roofs to tarps. It was spread on wounds in animals. It was anti-bacterial and, like a bandage, made a tough, flexible covering.

The sap in this stump has preserved the heartwood since the 1950’s, or before.

Local men would split heartwood from pine stumps into stove-size pieces. Then they would stack them on an iron plate about a yard square. They’d put a large iron kettle upside down over the plate with the pieces of pine inside. This was to keep oxygen away from the wood so it could heat without burning. They would pile slash (waste branches left from the logging) over the whole thing and set it on fire. They fed the fire, letting it slowly burn for several hours. The pine sap would heat up, trickle out of the wood, and collect on the bottom of the plate. The plate had a central groove to drain the sap away and into a pot or jar for storage.